Over the past two decades, Sierra Leone has faced a series of shocks: a civil war, landslides, Ebola, and the COVID-19 pandemic. These shocks have aggravated the learning crisis that the country’s education system faces—and dramatically increased the pressure on teachers to deliver high-quality support to children.

In this context, the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education and the Teaching Service Commission have come together to design a low-cost and scalable initiative to support the professional development of the education workforce. The initiative is school-based, technology-supported, and focused on early grade literacy and numeracy.

With funding from Dubai Cares, we have started to support the Government of Sierra Leone to build evidence to inform the development of the model under the Tich Mi Ar Tich Dem—’teach me to teach them’— programme.

In the first stage of the project, we plan to use a design-based implementation research approach. Under this approach, we will work with our partners to design questions to investigate the implementation process in a systematic way. In the future, evidence from this process will be used to strengthen the teacher professional development programme and improve our research instruments.

The rest of this blog post will look at what we have done and learned from the project so far.

What expectations do teachers have for continuous professional development?

In the first stage of the project, we have run focus groups with teachers in two schools outside of Freetown. In doing so, we have looked to understand past experiences of teacher professional development, the opportunities and challenges that teachers have faced, and how we can better support the education workforce in Sierra Leone.

What did we learn from these discussions?

- Teachers have participated in various professional development programmes in the past. The focus of these training sessions has included gender-sensitive pedagogy, learner-centred approaches, reducing corporal punishment, stress management, literacy, and the use of radios.

- Teachers felt very positive about professional development as they could increase their knowledge of skills, improve their ability to teach, access additional resources, strengthen student learning, and increase the enjoyment of teaching

- Teachers told us about a number of challenges including corruption, a lack of certification, a lack of funding, a lack of incentives such as transportation and refreshments, a lack of follow-ups, a lack of technology, and low salaries for teachers and trainers.

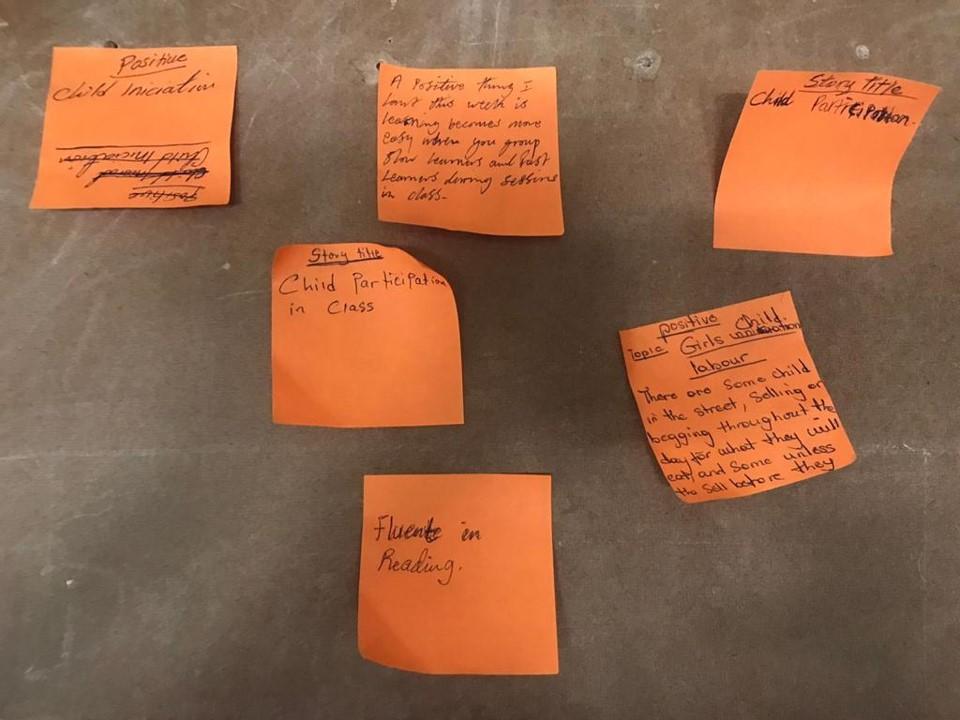

- Teachers explained how they believed the design of professional development programmes could be improved, including the key enablers and barriers that we have shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Emerging topics and themes from focus group discussions.

How should we introduce teachers and school leaders to school-based professional development opportunities?

The first stage of this project started with an induction workshop. Here, we introduced teachers from two schools to the use of teacher learning circles for regular reflection and professional development. In turn, these teachers were asked to try to set up teacher learning circles, with the option of choosing the best structure and timing for their schools.

So far, the research team has reviewed the effectiveness of the induction workshop through unstructured observations of the discussions, opinions, and body language of participants.

In doing so, we found that the following parts of the workshop went well.

- Teachers were highly engaged with the session, welcoming the structure and methods of learning;

- Teachers particularly enjoyed the ‘professional learning circle’ component of the programme;

- Teachers told us that they found discussions with their peers rich and valuable; and

- The use of a WhatsApp group to keep in touch with teachers, check on progress, and get quick feedback is a useful tool for the initiative.

At the same time, the team found that the following areas could be improved.

- Teachers did not fully understand the structure of the teacher learning circles, and we found a need to explain and model components such as regular check-ins;

- Teachers and government employees at a district level need to have clearer guidance on the purpose and content of workshops; and

- Teachers expressed concern about how they would regularly engage other teachers without incentives.

How can we support the delivery of teacher learning circles in Sierra Leone?

Following the induction workshop, we gave teachers two weeks to run teacher learning circles in their schools. After this time, the research team visited the schools to learn more about what worked and what could be improved going forward.

We have summarised the feedback from these visits in the table below.

Figure 2. Feedback from teachers on delivering teacher learning circles

What has the research team learned from this process?

During the first stage of the project, the team has regularly come together to share key learnings and reflections.

- Even though our first two schools are located in Western Area Rural, the setting is peri-urban as the schools are close to Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown.

- As teachers live close to Freetown, they may have had more exposure to teacher professional development programmes as many NGOs focus on Western Area.

- Similarly, the level of English of teachers in our two target schools may not reflect the levels of English of teachers in more rural areas. In the future, we plan to work with more remote schools.

- Teachers at one of our schools already participate in another teacher professional development programme that involves teacher learning circles and materials for early grade literacy and numeracy. Since we started our research, teachers have run two teacher learning circles. Now, teachers face unnecessary demands on their already heavy workloads.

- School visits—and other data collection activities—can add to the workload of teachers and keep staff away from the classroom. Now, we are working with the Teaching Service Commission and schools to limit the impact of our research on teaching.

- The success of the project depends on the collaboration of the Teaching Service Commission. So far, the Teaching Service Commission has supported us with guidance on the delivery of our research and communication with schools.

What do we plan to do next?

In the next stage of the project, we plan to take the following steps:

- We will work with more rural schools where teachers do not currently participate in an extensive professional development programme;

- Based on feedback from the first stage of research, we will work with teachers to improve the programme materials;

- We will explore the possibility of delivering materials on a tablet if the government has available devices;

- We will work with the Education Workforce Initiative to explore the role of school leaders in supporting school-based teacher professional development.